Demolition, Deconversion & Displacement

Green Gentrification in Logan Square

Logan Square in the early 2000s was not the trendy bar and restaurant destination it is today. Imagine you are a child growing up in the neighborhood at that time.

Like most of your neighbors, your family is probably Latinx. Maybe you moved from Mexico or Guatemala as a young child. Perhaps you are the first in your family born in the United States. Or maybe your family had been in Chicago for decades, moving from Lincoln Park as gentrification east of Logan Square made rents there unaffordable. On the weekends you play basketball on your street with your friends, dashing to the sidewalks when someone's father or tía shouts that a car is coming.

As the weeks go by you notice fewer abuelitas sitting on their front porches when you walk down your street. When you start school in the fall, several of your friends are no longer enrolled. The corner store you always bought a treat at after school is no longer open. When you get home, you pull a real estate flyer off of the fence in front of your building. It promises good sale prices for homes in your neighborhood.

One Saturday you sit on the curb with a friend, talking about your favorite Christina Aguilera songs. Her mother rounds the front of a moving truck parked in front of her house and tells your friend it's time to go. Your friend promises she'll see you tomorrow. You won't see her again.

Over 20,000 Latinx families have left Logan Square in the last two decades. What's known as "green gentrification" is responsible in part for this mass displacement of Latinx, low-income, and renting families. Without housing policies put in place, new green spaces and parks like the 606 Trail attract affluent developers, bring in wealthier residents, and raise property values. These events lead to the demolition and deconversion of naturally occurring affordable housing and, in turn, displacement.

Families in Logan Square, both the ones who are displaced and the ones who remain, feel the effects of displacement. "My son goes to McAuliffe School," said Monica Espinoza, a Logan Square Parent Leader. "We're losing enrollment every year because the people who move into our neighborhood, they're not bringing their kids to our neighborhood schools. We want our schools back, we want our neighborhood back. We were here before anyone else."

Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing

Naturally occurring affordable housing refers to rental housing that families can afford without rental assistance. In Chicago, naturally affordable housing units are typically found in two- and three-flat buildings.

While subsidized buildings with affordable housing and rental assistance can help address the affordability crisis in Chicago, naturally occurring affordable housing benefits the most families. For a long time, families in and around Logan Square benefited from the large stock of two- and three-flat buildings.

Many Latinx families in Logan Square, Hermosa, Humboldt Park, and Avondale paired up in such buildings. One family would own the building and live in one unit while another family would rent the other.

Demolition of two- and three-flats in these neighborhoods often leads to deconversion. Buildings that could affordably house multiple families are torn down and replaced with more expensive single family homes. Together, demolition and deconversion lower the availability of affordable housing in a neighborhood and price families out.

In addition to the impact on housing prices, demolishing housing also poses environmental and health hazards. Tearing down a house or building releases clouds of dust in the surrounding area. A 2018 WBEZ report found that Chicago officials rarely enforced existing laws that require contractors to manage potential poisonous contaminants, like lead and asbestos, that can be released during demolitions. One Chicago study found high levels of lead up to 400 feet away from construction sites in the city.

Demolishing Affordable Housing in Logan Square

Early 2000s and the Housing Crisis

In the 1980s and 1990s, Latinxs from across the Caribbean, South America, and Central America immigrated to Logan Square. The neighborhood and surrounding areas were home to largest population of Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Cubans, and Central and South Americans.

Prior to the 2000s, there was not a lot of capital investment in Logan Square. Disinvestment made the neighborhood a relatively cheap place to live. Organizations like Palenque LSNA (formerly the Logan Square Neighborhood Association) formed to fight for resources for local families and schools.

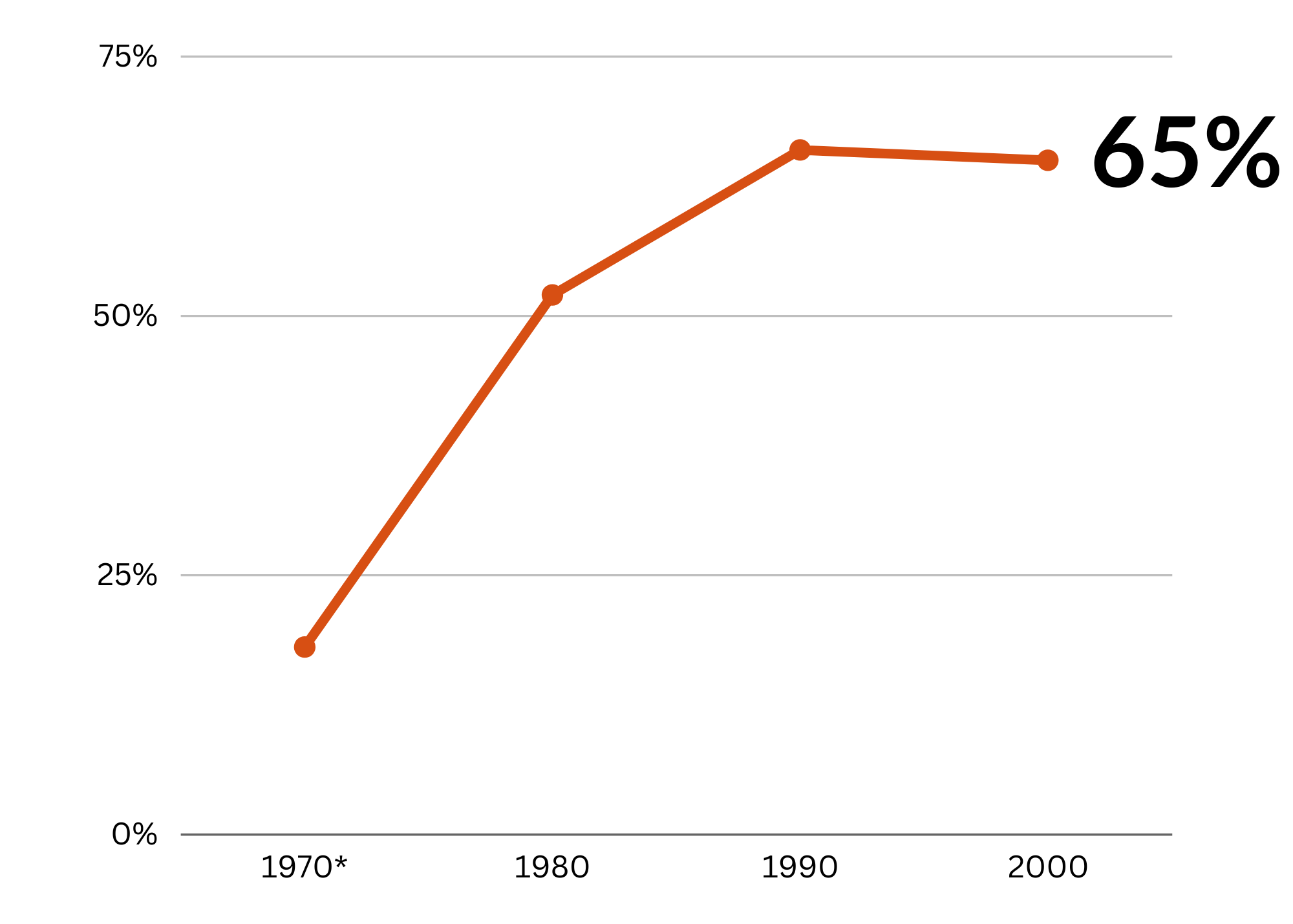

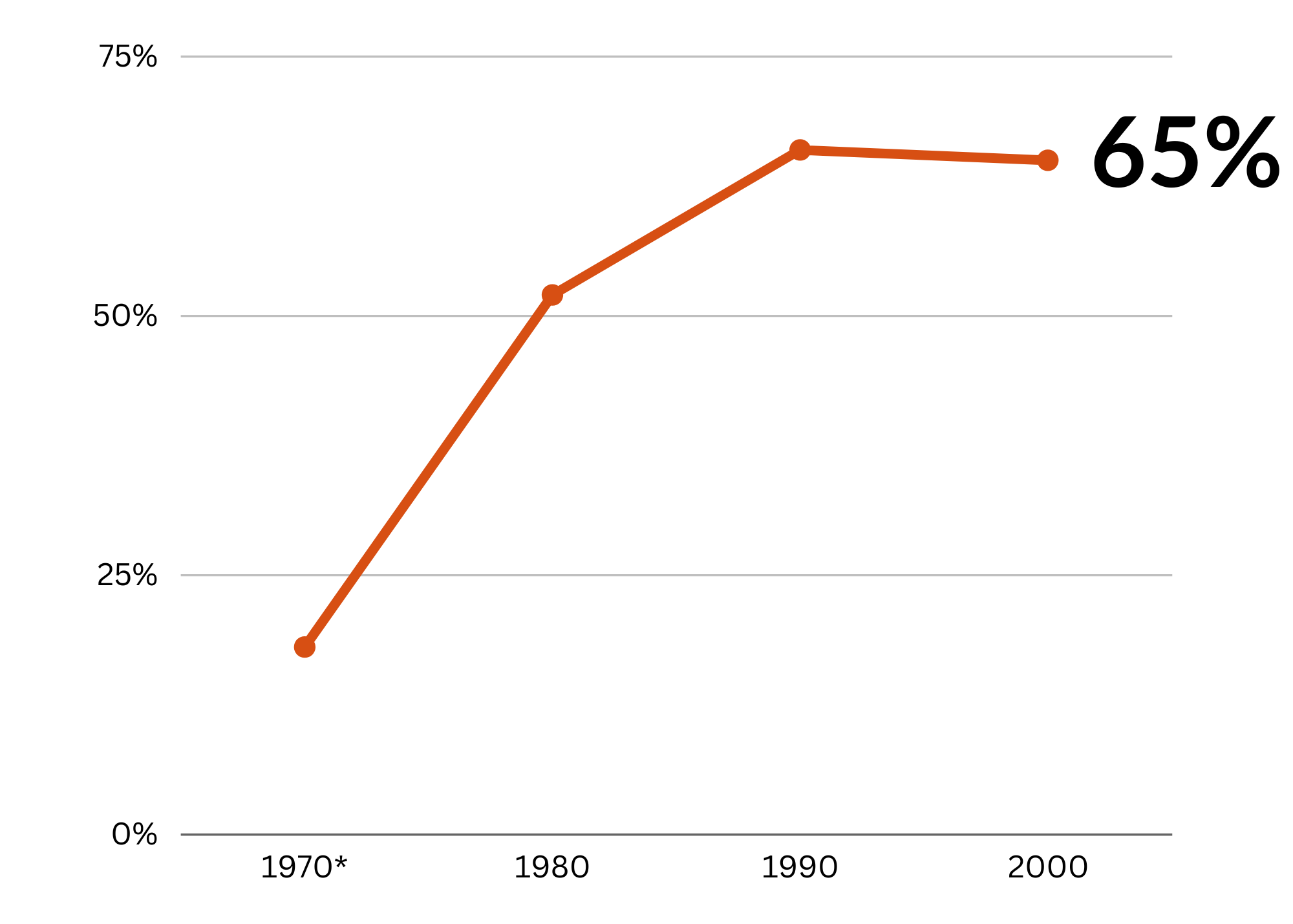

By the year 2000, the Latinx population in Logan Square had reached 65%. Around this time, gentrification processes began in Logan Square. Many rental buildings were de-converted into condominiums, forcing families to buy or, more often, leave their homes.

The 2008 housing crisis brought a temporary reprieve in deconversion and luxury development, but it also created a large stock of foreclosed housing available at a low cost.

As the recession began to calm down around 2012, development in Logan Square took off.

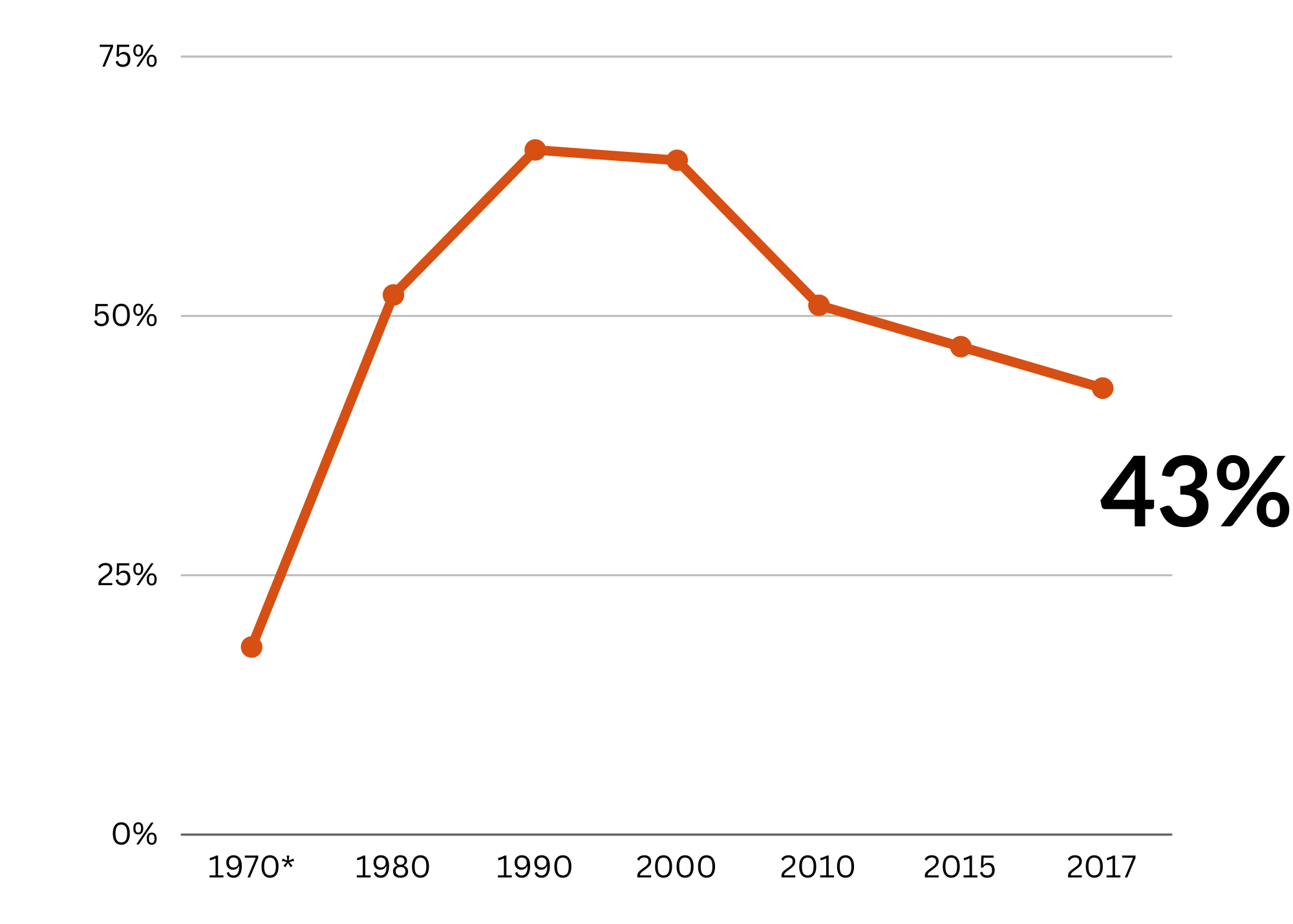

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

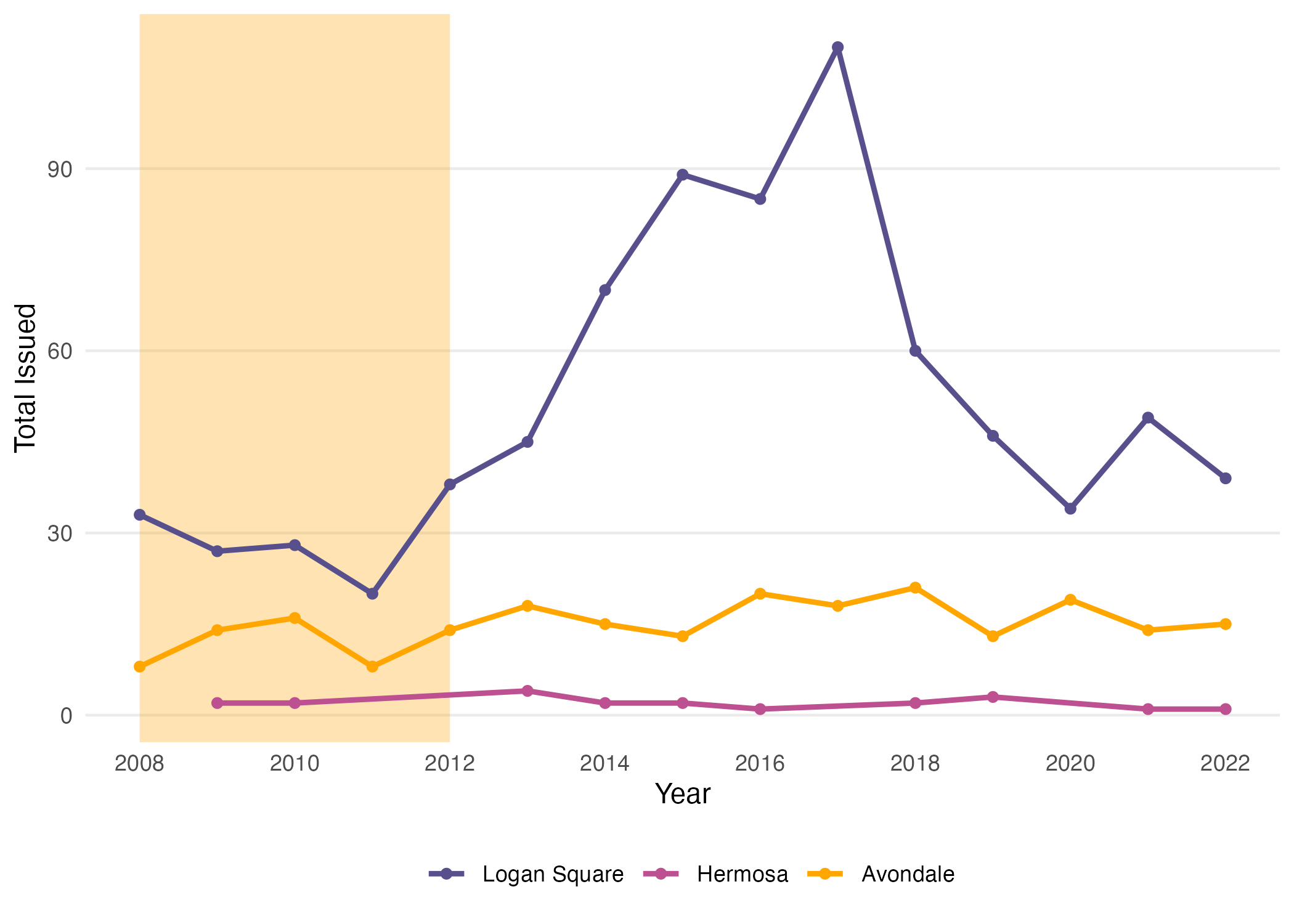

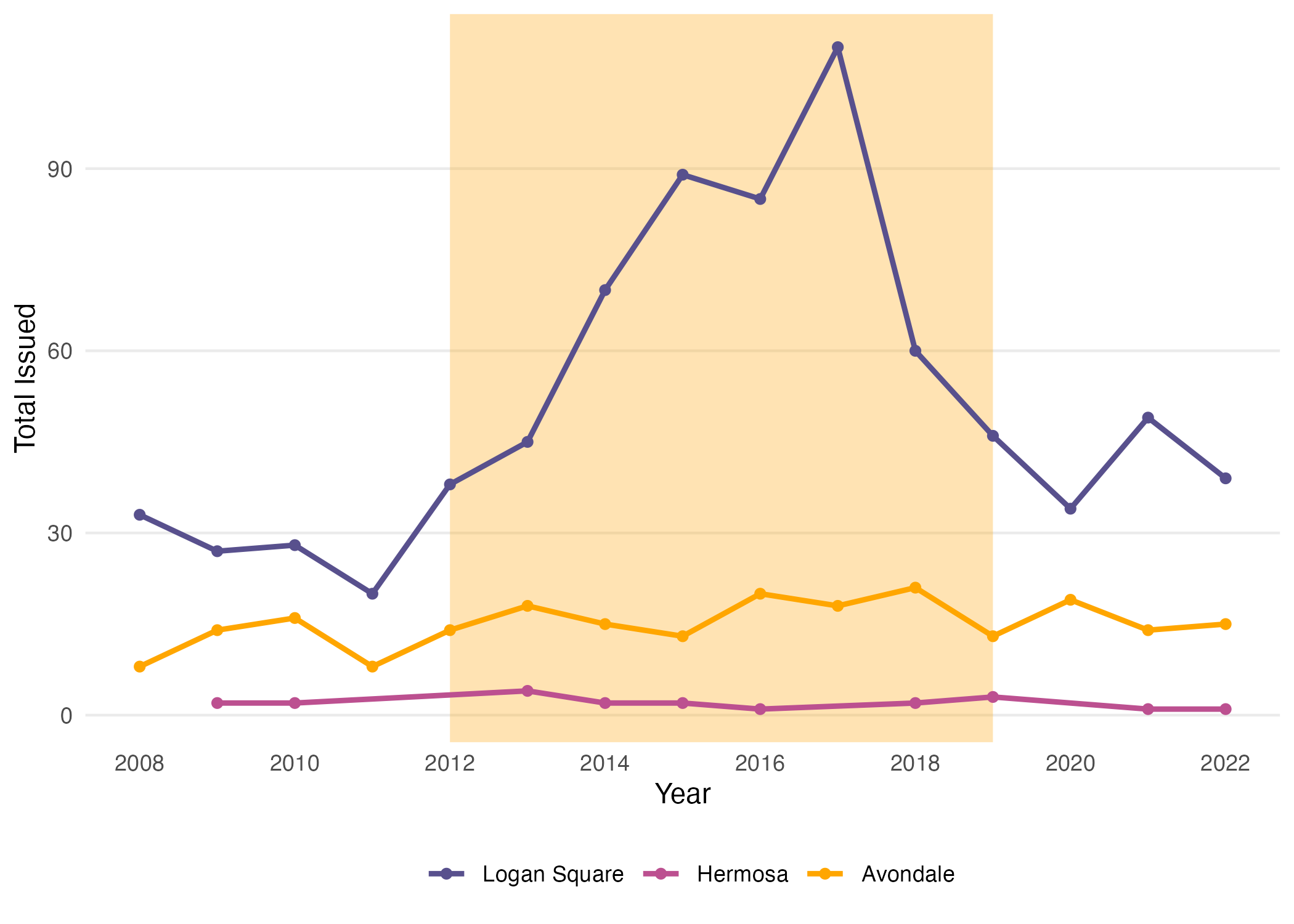

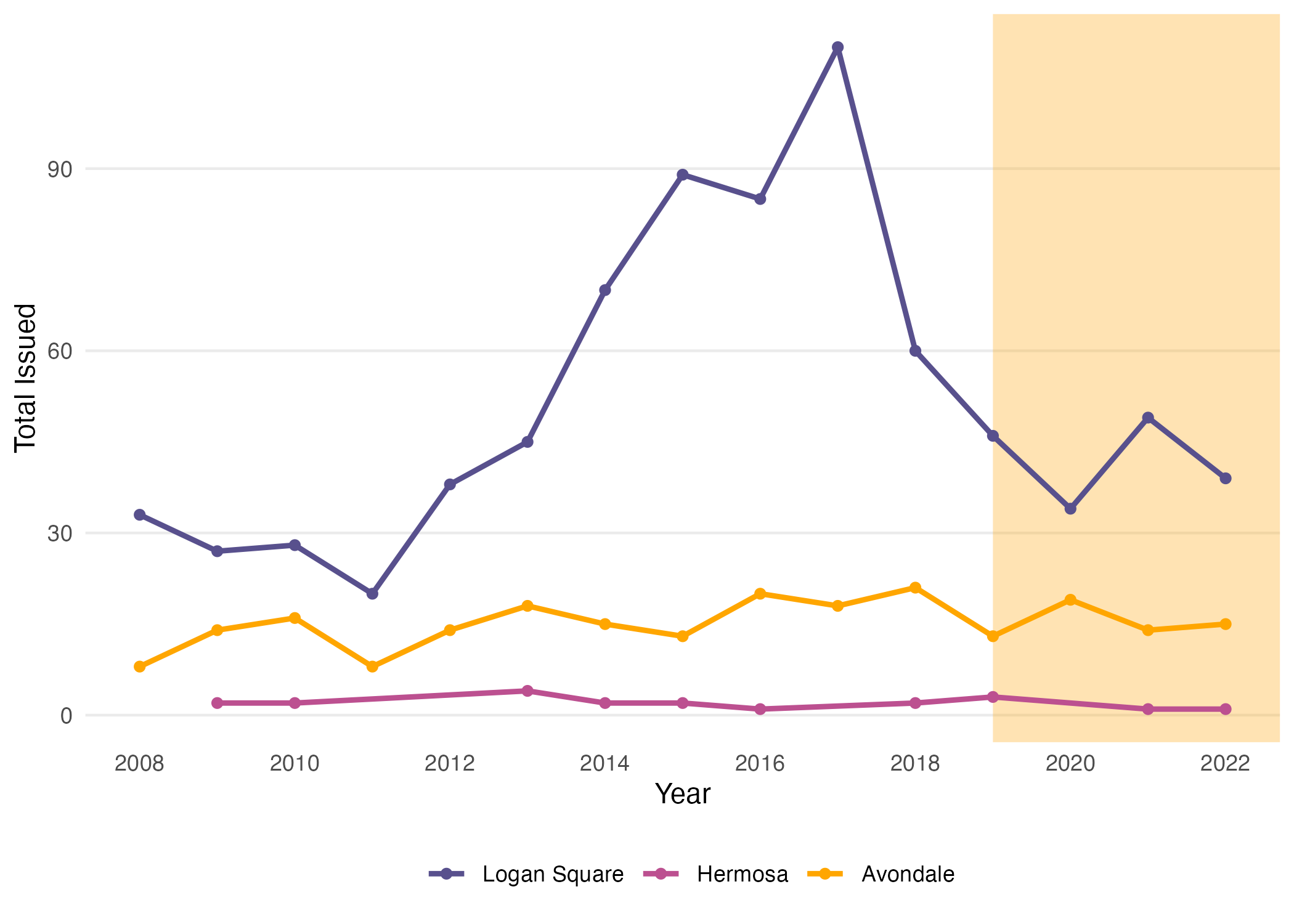

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

The Acceleration of Gentrification (2012 - 2019)

The early 2000s had already seen waves of development that had swept through Lake View, Lincoln Park, and Wicker Park begin to creep into Logan Square.

After the housing crisis, developers realized they could buy foreclosed buildings or affordable two-, three-, and four-flat buildings, demolish them, and sell single-family homes or luxury buildings at a much higher price.

According to a Housing Studies report from DePaul University, affordable rental units in Logan Square and Avondale dropped by 15.3% between 2012-2014 and 2012-2021. By the later period, only 25% of rental units in the neighborhoods were considered affordable.

During this period, property taxes increased, hip bars, restaurants, and businesses catering to young, White professionals replaced older businesses that served the area's Latinx families.

By 2017, over 20,000 families had left Logan Square and the Latinx population dropped to 43%.

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

Percent of Logan Square residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino (*in 1970 reported as persons of Spanish language)

Since 2008 789 buildings have been demolished in Logan Square. Many of those buildings were 2 and 3-flat naturally affordable housing

Demolitions (2008-2010)

Demolitions 2011-2013

Demolitions 2014-2016 (the 606 is built)

Demolitions 2017 to 2019 (peak of demolitions)

"Instead of celebrating [my sister's quinceañera], we were packing the U-Haul, we were packing our lives. For a couple of weeks, my family and I were homeless."

The Impact of The 606 Trail

Prior to the early 2000s, the city had largely disinvested from Logan Square and surrounding neighborhoods. Logan Square was one of the most park-deprived areas in Chicago. Community organizations in the area dreamed up the idea of a parkway an abandoned elevated railway along the southern border of Logan Square.

This idea became the Bloomingdale Trail, aka The 606. The plans for the trail ran through West Town, Logan Square, and Humboldt Park. Higher-income, majority-White neighborhoods made up the east side of the trail. Lower-income, primarily renting, Latinx neighborhoods made up the west side.

Rahm Emmanuel's administration picked up the idea of an elevated parkway on the northwest side of Chicago, championing the project and accelerating its completion. Plans moved forward without thought about how the new parkway would affect rent and housing prices for existing residents.

Investors and developers took advantage of the many foreclosed, affordable rental buildings near The 606 in anticipation of the trail opening. They tore down and deconverted many buildings into single-family homes and luxury condo buildings.

Housing prices on the west side of the trail in Logan Square and Humboldt Park have increased by 48.2% since the brail broke ground and rose an additional 9.4% after the trail opened (according to a 2016 DePaul Housing Studies report).

Youth and parents have been some of the biggest advocates for addressing gentrification and the housing crisis in Logan Square, Avondale, Hermosa, and Humboldt Park.

"We want to work with our local aldermen to create an ordinance or policy to regulate these teardowns and to bring the money back into affordable housing in both Logan Square and Humboldt Park and reassure our families' spots in the neighborhoods we helped build."

Equitable Development

In response to the demolition of affordable housing in and around Logan Square, a coalition of residents, community organizations, and local leaders have developed plans to slow gentrification and pursue equitable development in Logan Square, Avondale, Hermosa, and Humboldt Park. They have been fighting for the last two decades for their right to stay in the neighborhood they call home.

Equitable development involves processes that ensure low-income and communities of color can participate in and shape the economic development and growth of their neighborhoods. Equitable development ensures that investments will benefit existing residents and not increase racial and socioeconomic inequality.

In January 2020, the Chicago City Council passed a moratorium on issuing demolition permits in the area around the 606 in Logan Square and Humboldt Park for 6 months. The council extended the moratorium, stopping demolitions for a total of 14 months from February 1, 2020 to April 1, 2021.

In January 2021, Mayor Lori Lightfoot introduced and passed a deconversion ordinance covering the areas surrounding the 606 and another area in Pilsen. The deconversion ordinance prohibits single-family homes from being built without a zoning change on blocks with greater than 50% multiple-unit buildings.

In March 2021, the City Council passed a Demolition Surcharge Ordinance for areas around the 606 and in Pilsen. The ordinance requires property owners to pay a $15,000 fee before demolishing a detached house, townhouse, or two-flat and a $5,000 fee before demolishing a multi-family building.

Since these efforts were put in place, demolitions around the 606 trail have declined by 88% since their height before 2020.

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

Demolition permits issued in Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2008-2022). Data from the City of Chicago.

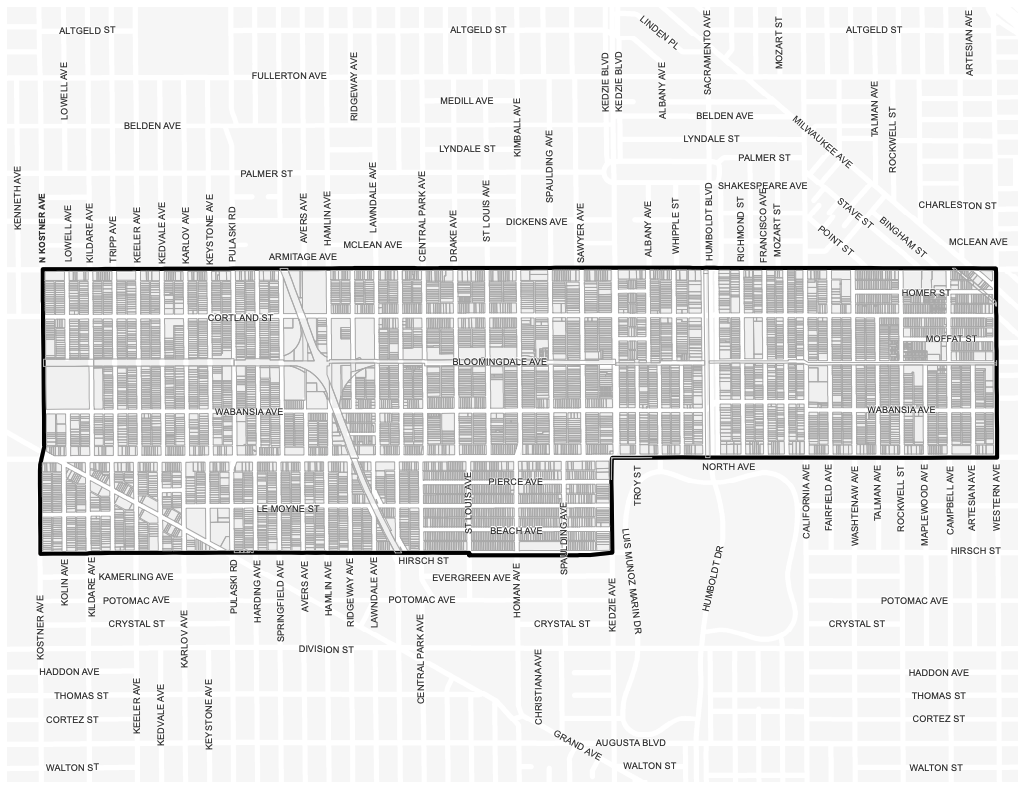

Current Anti-Deconversion and Demolition Surcharge Area

Source: City of Chicago

Source: City of Chicago

Peak of Development (2017 to 2019)

Lower Demolition Period (2020 to 2022)

What comes next?

The fight for the ability of Chicago's Northwest Side families to remain in their communities cannot stop here.

Youth, parent, and community leaders are asking elected officials and residents of Chicago to support the following programs and policies that have been proposed:

- Extend the demolition surcharge around the 606 and in Pilsen to protect naturally occurring affordable housing and rental units

- Establish robust community-driven zoning processes like the ones set up in the 35th Ward

- Invest in Here to Stay and other community land trusts that make homeownership possible and affordable long-term

- Support more housing cooperatives in Chicago that can provide accessible pathways to home ownership and keep housing prices from escalating

- Pass the Bring Chicago Home Referendum, which would create a permanent revenue stream to build desperately needed permanent affordable housing to combat homelessness

- Invest in more Equitable Transit-Oriented Development projects to ensure that low-income, Black, and Latinx Chicagoans can live near public transit that provides easy access to jobs and services.

While gentrification and displacment have harmed Logan Square, Avondale, Hermosa, Humboldt Park, and other communities across Chicago, there are many opportunities for equitable development. The message from the families that remain is clear: we will come together and we are here to stay.

"I feel protected by the power of the community. Maybe we don’t have peace of mind, but we have hope and we can pass that hope along. I want to stop surviving. I want to live a free life. Starting with ourselves and our schools, we can change the world."